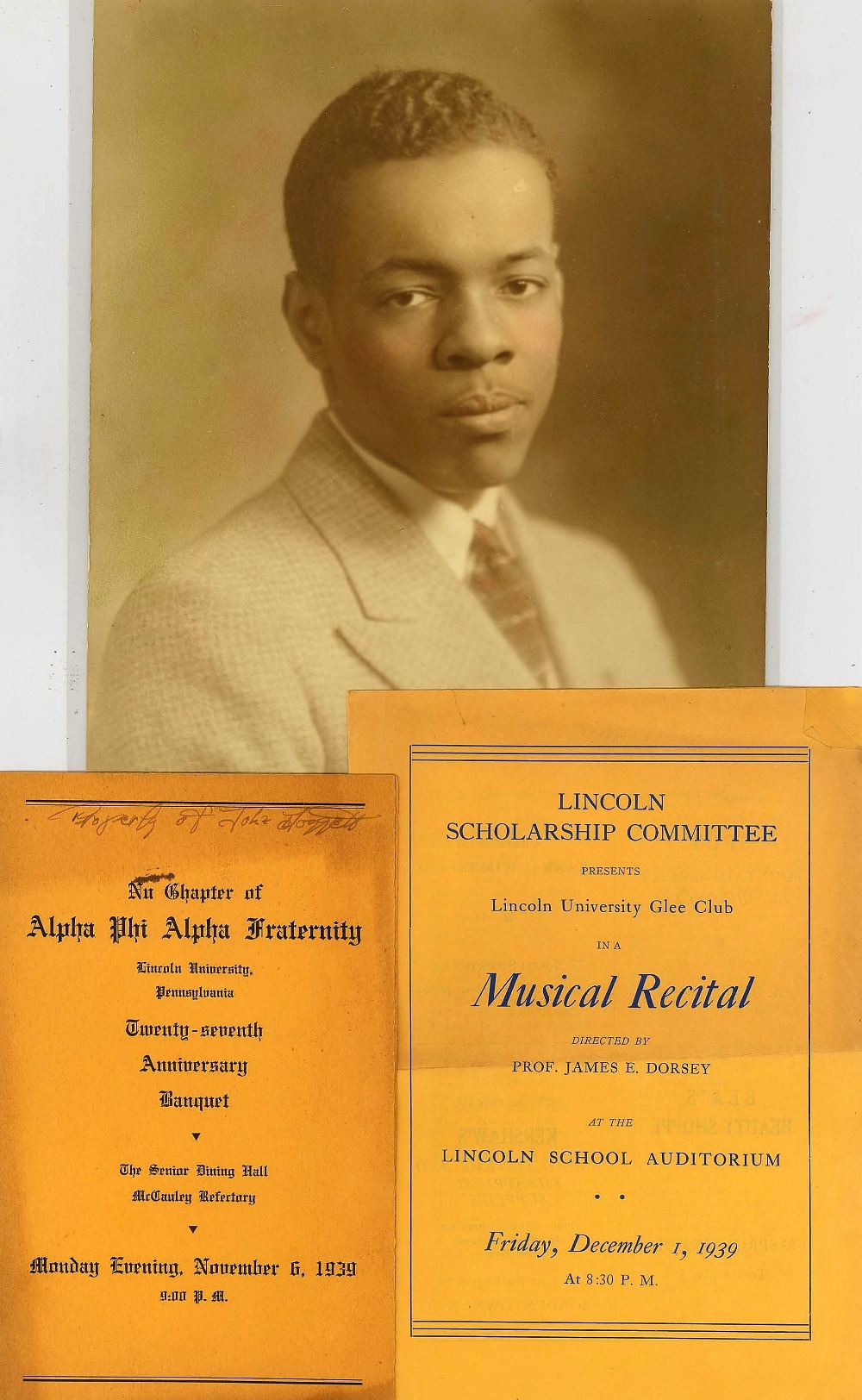

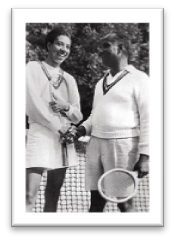

Dr. Robert W. “Whirlwind” Johnson was the force behind integrated tennis. The former football All-American built a tennis dynasty in Lynchburg, Va. that produced the first two African-American Grand Slam champions, Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe. On August 24, 1946, Dr. Johnson and his good friend Dr. Hubert Eaton witnessed the future of world tennis: Althea Gibson. That day, they vowed to each other and Althea to break the game’s color barrier and develop a Grand Slam champion. They made many personal and financial sacrifices to achieve this end. Althea later declared, “I owe the doctors a great deal. If I ever amount to anything, it will be because of them.” Althea integrated Forest Hills in 1950; seven years later, she won it.

Dr. Johnson, a human dynamo, did not hesitate once Althea’s course was set. He immediately spun into action and established the Junior Development Tennis Program under the aegis of the American Tennis Association. Each summer, he invited dozens of talented juniors to train on his backyard court. They traveled the country, winning titles and making history. In 1953 (Ashe’s first year at camp), the USLTA extended an invitation to Dr. Johnson’s team to play the Nationals at Kalamazoo, M.I., using ATA credentials. That same summer, Bobby Riggs conducted a clinic on Dr. Johnson’s court. Five Grand Slam champions, Riggs, Gibson, Ashe, Pauline Betz-Addie, and Manuel Santana, would succumb to the charisma of this man and grace his Lynchburg court with their presence. He embraced diversity as an integral part of America’s future; his camp was open to all races. It was the precursor to today’s tennis academy, with one exception: Dr. Johnson ran it with his own money. Players traveled first class. In the spring of 1951, he integrated his first junior event; the USLTA Inter-scholastic Championships.

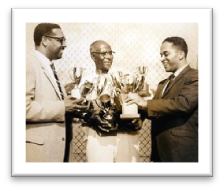

Dr. Johnson, a soft-spoken man of unflinching determination, carried a “big racquet” and quietly “aced” the tennis world. He had the uncanny knack of influencing people and organizations to buy into his vision of a new tennis world. This unlikely pioneer was so influential in the game that he could get black players into the main draw of the US Nationals at Forest Hills. This period of unprecedented opportunity for blacks on both the junior and adult circuits of the USLTA lasted until Dr. Johnson’s death in 1971.

“Dr. J” as players called him, was more than a coach. He was a teacher and role model. He was a talent scout par excellence who could spot and develop untapped potential. He preached perseverance, patience, sportsmanship, etiquette, humility and hard work. He valued education and garnered for his campers’ college scholarships through his network of associations established during his college football playing and coaching days. His lasting legacy is that he made tennis accessible for everyone by relocating it from private, segregated country clubs to integrated public facilities.

Tennis historians have lauded the noble efforts of Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe in breaking down racial barriers. Without the guidance of Dr. Johnson, however, Gibson, Ashe or countless others might not have succeeded so mightily. Dr. Johnson trained, coached, and mentored African Americans from his home in Lynchburg, Virginia for more than two decades. He established a crucial Junior Development program for the American Tennis Association, worked tirelessly behind the scenes to provide competitive opportunities for all competitors, and emerged indisputably as a towering figure in the evolution of the game across the American tennis landscape for three decades (1940-1970) and changed tennis forever.

For more information, visit www.whirlwindjohnson.org.